| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

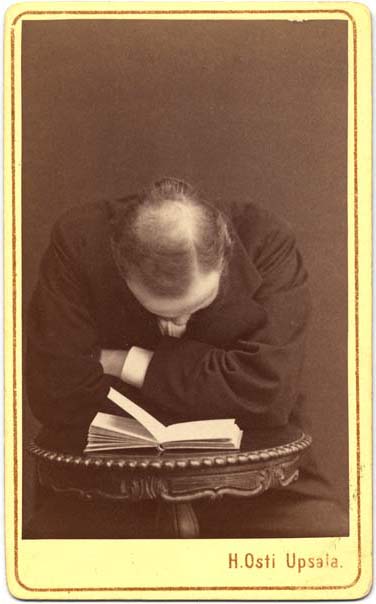

Reading Like A Writer by n a sulway |

It is often said by any writer who is asked to give advice to other writers that the first and most important thing a writer can do is read. My personal favourite meme that expresses this idea is:

I think this is my favourite because I am constantly and perpetually amazed by the number of writers I meet – particularly those who are still on the first leg of their Odyssean writing journey – who spend more time and energy reading and writing their own work than they do reading the work of others, especially those with more experience than they have yet managed to accure. It is also a personal favourite because I have come to recognise that one of my core writing beliefs - one of those defining truths that forms part of my philosophy of writing - is that the only true way to keep growing and improving as a writer is to perpetually measure one’s own work against the work of other writers, to constantly be in the process of learning what good writing is. To read writers whose work terrifies you with its grace, whose work inspires you with its seeming ease, with its emotional clarity, with its lyricism or humour, its tensile strength or raw energy. And, perhaps equally, to read the work of other writers who disappoint you, who are struggling to say what they mean, who bore you and frustrate you. I am particularly amazed by those fledgling poets I meet who don’t read poetry, fiction writers who only read non-fiction, crime writers who only read science fiction, novelists who only read the newspaper. I cannot imagine a musical equivalent: I cannot imagine a jazz musician who refuses to listen to jazz, and proclaims their ignorance with pride. It seems to me that of all the different kinds of artistic practitioners in the world, it is only writers who are proud to proclaim their naivete of their own artform. I won’t go into why I think this might be so – I have my theories and perhaps you have yours – suffice to say that I believe it is indefensible, particularly in a writer who is still learning their craft (that is, one who has only been writing for fifty or sixty years) to stop reading, to concsciously decide to stop learning, and then to proclaim their laziness and foolishness from the hilltops. I think, too, that that meme about time, reading and writing appeals to me because it expresses so succinctly the necessity, in order to become a better writer, to let go of your ego. To embrace that your writing is what it is. Few things distress me more than that common expression by all kinds of writers – good, bad and indifferent – that they write purely for themselves. To give themselves pleasure. For me, this can only ever be part of the equation of creating a book. A whole writer has, I think, a more holistic approach. The writing (verb) is for the author’s pleasure, - yes yes yes, as Molly Bloom once said - but the writing (noun) is for someone else. It is a gift, to be given away freely, with that particular and thrilling sense of relinquishment and satisfaction that comes from anticipating of someone else’s pleasure. Of having made their day. Related to this, for me, is the sense that a good writer, is far more likely to be someone for whom the pleasures of reading are still real. Still sustaining. They will often gain more pleasure from reading someone else’s perfectly-formed sentences than their own precisely because someone else’s writing is a thing given to them without history, without effort. Someone else’s writing is a gift. A profound act of generosity. Other people’s writing is a source of solace and amazement and wonder and awe and envy: inspiration and nurturance. I believe that a good writer reads: voraciously, hungrily, not just because it is part of their work to do so, but because they are in love with words, with stories. A good writer reads because not to read would be a kind of death. Because, as Susan Sontag once wrote: “Reading, the love of reading, is what makes you dream of becoming a writer.” So, this is my personal prescription for the nuts adn bolts, daily lifework of becoming a writer (and writers, no matter how impressive their publication histories, are always in a state of becoming): Read. Of course, there’s more to it than just reading. This is not the casual, grazing reading of a non-writer seeking largely pleasure and distraction. To read as a writer is to engage in an activity that goes beyond the semi-distracted, immersive uncritical activity of reading undertaken by a lay reader. To read as a writer is to go deeper into the text, to discover deeper and more complex pleasures and, yes, more dissatisfactions, more of a sense of the flaws and possibilities not only of the work you read, but also – crucially – of your own work. It is to read work that infuriates and frustrates and eludes you and to keep going, to pay attention and struggle onwards through the text, because there is something to learn from every other writer’s success, and every other writer’s failure. There is as much, perhaps more, for you to learn in reading books that are successful – or have been judged so by others, consistently – but are not to your taste, as in reading works that appeal to you for personal, private or emotional reasons. I believe that reading as a writer is about going beyond your comfort zone, it is to force yourself to grow beyond the ordinary response to a book of liking or disliking it. Of giving it a 1-5 star rating and letting it go. To read as a writer is to give up personal taste as the one true measure of a book’s success or failure, and develop a more complex and nuanced sense of what a book should and can do. Along with Pound, I believe that if a book is truly ‘art’ (that is, if it is truly ‘good writing’) then good reading practice will reveal the many and varied pleasures of that text. That is, if you are a good enough reader, there are pleasures – intellectual, aesthetic and emotional – to be gleaned from any work of art: any good piece of writing. The key lies in developing your readerly skills. I won’t bang on about this: it is my experience that most people recognise this to be true at some level. It is why even the most inexperienced readers often cite poems or books they were ‘taught’ at school as their favourites: these are the texts they really read. The texts they took apart and put back together. The texts they have not just an immediate, emotional response to, but a technical and aesthetic appreciation for. Despite the groans of high school students encoutering Shakespeare for the first time, or forced to parse a poem they once loved without knowing how or why it was poetic, it is not true - I think - that examining how a thing is made makes it less pleasurable. Really good writing withstands this kind of engagement; benefits from it. Really good writing just gets ‘better’ when you understand how and why it’s good. As a reader, your sense of the effort involved to make it just so increases your admiration for the ease with which it can be read. Really good writing sometimes exceeds your ability to understand why it is good: it is more than the sum of its parts. The thing is not to give up, even if this is so, but to read harder, to read deeper, to experience that pleasure again and again until you know instinctively why it is good, even if you cannot yet know it intellectually. The First Chapter: examining the building blocks of narrative There are five building blocks of a book, all made of language:

Make note of the way the book you are reading deals with these elements. Is there a broad vocabulary, a slim one, a prosaic use of language, a variant one for different characters or types of prose (expository, scenic, etc)? Are the writer’s sentences generally short and crisp, variable, ambling, vacillating? Do they use all of the different types of sentences, or tend to prefer a particular kind of sentence? A handful of particular kinds? How many different kinds of sentences do they use (of the four basics: simple, complex, compound, and compound-complex)? What use do they make of verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs? What kinds of sentence structures and word choices do they use in dramatic scenes, in character-building moments, in expository prose, in linking passages? What poetic devices do they use (repetition, rhythm, etc)? Are they strictly grammatical or more casual, more instinctive? How do they mark silence in a text (one of the most difficult things to do)? How long are their paragraphs? How much do they vary? How are their paragraphs structured? How do they show the passage of time? How do they get their characters from one scene to another? How do they reveal character? How do they reveal setting? What is the narrative structure of the chapters? How long are the chapters? How much information is conveyed in each chapter about the setting, characters, action, themes? What similarities (if any) are there between the beginning and ending sentences of their chapters? Paragraphs? You can discover amazing things in doing this kind of analysis. Things that will surprise and amaze you in quiet and earth-changing ways. My partner, in the throes of doing some research on crime fiction, this week brought me their new writerly discovery: Scandinavian crime writers almost always start with the weather. It is snowing, or raining, or warm, or sleety, but it is weathered. At the end of a week of reading just the first chapter of a book - when you know it almost well enough to recite it - write down what you think you can expect from the rest of each the book: plot, character development, style/voice, structure, themes, etc. Anything you can think of; anything you notice you are expecting from the rest of the books: boredom, thrills, beautiful sentences, long paragraphs, a broken heart, a thrill a page. Write down whether you are keen to read on, and why you are, or aren’t. This is a great way to developing a real and concrete sense of why first chapters matter. First pages, even. At the beginning of your career – perhaps having not yet sold your first book – they matter perhaps more than they will ever matter again in your professional writing life. At this stage your readers – agents, publishers and then reviewers and public readers – have to be seduced into reading further than the first page. They don’t know you, and there are plenty of other interesting writers out there for them to meet. There is lots of competition. If you haven’t got them ‘at hello’, then you probably haven’t got them at all. Turning the Page WHAT do you know about this story/character/theme/other aspect of the novel? [That is, ask yourself what the author has conveyed to you in some way, even if you’re not sure why you think you know this thing], and then ask: HOW do you know this? [That is, how did the author/text show/reveal to you what you think you know. How subtle or obvious was the revelation?] Think about the things you take for granted when you read purely for pleasure. At the end of the first chapter you might think you know, for example, the following kinds of things about a particular novel:

When you read just for pleasure, just to enjoy the story and allow the writing to be in the background, washing over you, you would still notice these things, and perhaps even wonder about them as you go about your non-reading life. You might wonder about them in the way you wonder about people you know: will she leave him? Why or why not? What will their child grow up to be like? How difficult would it be to be a painter/artist and not know that you are bad – not have any sense of it – and have your life partner know it and not tell you? Do I like this book? Who would I recommend it to, or buy it for as a gift? Why them? The writerly, attentive reader goes deeper: asking themselves how they know these things. It is highly unlikely, in a book of any intelligence or complexity, that all of these things have been conveyed to you in bald statements, particularly those things that are about the conditions within the couple’s marriage. The next step in your reading might be to think of these things more cynically, or externally. Ask yourself whether the perceptions you have of the characters and their world are a product of the point of view, for example. If the novel is told in first person, I would hazard to say that the non-existent novel I described above is probably not being told from the viewpoint of the husband, but from that of the wife or someone close to her – a lover, a sister, friend or parent. Ask yourself why it’s being told from their point of view: what is hidden, what is on show? How does their psychological make-up, their sense of why the story is being told, affect what the reader learns? Why has the author chosen this point of view? What freedoms and limitations does it allow them? Ask yourself more complex questions about the point of view - go beyond the technical and ordinary assessments of first or third person, present or past tense. Ask yourself how much distance there is between the time when the story is being told and when the events are occurring. Ask yourself how much distance there is between the narrator and the author, between the narrator and the characters. Think about how time is being managed in the novel: what models of consciousness are being assumed in the writing of character. What politics or social structures inform the writing of class, gender, wealth or business. What happens to the story and its characters, themes and styles if you imagine it set in another place or time, or change the genders of characters, or their ages? Doing this kind of mental exercise can reveal the stereotypes and clichés of the text, and reveal the extent of their situatedness. As you work, you might develop your own strategies or methods for taking that imaginative step backwards from micro-reading – analysing sentences, paragraphs, etc – to more macro-reading: reading for the big picture. When considered on a whole-book scale, what limits does third person represent? What opportunities? What limits does the choice of vocabulary/style represent? What opportunities? From Reading to Writing This is a lifetime’s work, so don’t torture yourself too much about getting it nailed down today, this week, this month or even this year. For a writer, analysis of other people’s writing has its natural end in your own writing, in the lifelong task of learning what good writing is in order to make some of your own. I believe that any definition of ‘good’ writing must start by recognising that definitions of what constitute ‘good’ art of any kind are a mysterious blend of the external and absolute (the things perhaps almost all writers adn readers would agree on), and the personal (that is, the things only you and a more select group of writers and readers would agree on). Your definition of good writing is – and should be – elastic and ever-changing, flexible enough to grow when you encounter new works that shift your sense of what is good, and firm enough to give you a concrete sense of what you’re trying to achieve in your own work, to give you confidence that what you are producing is good writing. The point of acknowledging that definitions of good writing are absolute is that it allows you to own your sense of what you are trying to achieve. To be clear and unashamed in being able to say: What I value in a book is x, y and z. For me, this kind of personal stance is far more honest a definition than the more absolute versions you might have heard from the worst kinds of critics, ie: “a good book is always x, y and z”. Definitions of what constitute good writing are not static or absolute: they are conditional, evolving and personal. Underpinning this task of developing your own personal definition of good writing is the assumption that you cannot write well unless you have a sense of what writing well means. That you will never know whether your writing is good enough unless you have some concrete, explicit sense of what good writing looks like. My sense is that too many of us get bogged down in trashing writers we don’t like, and lauding those we do, without stopping to really consider what our criteria for these divisions are. In dismissing works we don’t ‘like’ we often make sweeping claims about what we do or don’t like that, on reflection or analysis, turn out not to be true, or are too bald and simplistic. We find that we have said things we don’t really mean. Things like: I don’t like action films; or, I’m bored by romance stories. The point of developing your criteria for ‘good writing’ out of close reading and analysis is that it will become more complex, more nuanced, more open than those kinds of first not-quite-right judgements, and more sensitive to the multitude of ways in which writing can be ‘good’. It is also about being aware of and understanding that while there will be some overlap in your personal definition of good writing with other readers and writers, there won’t be – and doesn’t have to be – any single ‘right’ answer to the question of what good writing is. It is an ideal tool for learning to respect and understand that there is room in the writing and publishing world for all kinds of writers and readers, for all kinds of books. It is an ideal tool for learning to be a better and more understanding editor, too, since reading for the internal magic of book - for what it gets right and for where it’s going off-key not in absolute terms, but in its own terms - what I call reading from the inside out - is an essential skill for editors. Everybody is on a slightly different journey as a writer, and has different tales to tell about the monsters they have met, different destinations they are heading towards, a different sense of what it is they are trying to achieve. From Writing to Rewriting You do need to know how to recognise when the work is finished, and let it go. In other words, your criteria for good writing gives you a foundation from which to focus the work you need to do during your whole writing life: learning about writing, and what aspects of writing you could usefully learn more about to write your next book, and the next book, and the one after that. You might find, at some stage, that your writing does not meet your own criteria for good character development. The close reading and reflection skillset outlined in this essay gives you the tools with which to find out what aspects of character development your work falls down in; what ways your criteria might need refining or reconsideration to enable you to better understand how your character development is flawed; how you can rewrite or edit your work until it does meet your own informed and growing sense of the criteria for good writing/character development. These strategies for developing your own criteria for good writing out of a lifelong practice of close reading and analysis of writing are some of the ways in which you can grow to become a more skilled writer, reader, rewriter and editor of your own work. Together, they form a cycle of reading, thinking, analysing, writing, re-writing and reading that focuses you on improving your own work through the lifelong, unanswerable quest for a definition for good writing. It is a basic toolkit of reading, thinking and analysing that you can continue to build on in order to continue to develop your practice independently. About the Author N A Sulway is an author. She lives in Queensland with her partner, and children. You can find out more about her, and her work, at her website.

|